The Yaeyama islands

The main Yaeyama island, Ishigaki, where the airport is located, is a similar mix of tropical lushness and workaday architecture. Ishigaki City, the capital, has a laid-back friendly feel, and is a contrast after frenetic Tokyo.

Liz Boulter

Smartphones are wonderful things. After a simple lunch at the only restaurant in the tiny village – fried rice, and miso soup with fish and vegetables – we trotted out one of our few Japanese phrases. "Gochi so sama deshita." (Thank you, that was a feast.) The cook beamed and said something to our guide. His English was not much better than our Japanese, but technology came to our aid. Tapping his phone he showed us on screen the translation of the cook's words: "Did you like it?" To smiles all round, we managed unaided a one-word reply: hai (yes).

Such minimal communication felt very special: this was the wildest corner of the wildest island in Japan, Iriomote. Why would anyone speak English? The pearl-farming village of Funauki is home to about 50 people, and reached by ferry across a bay from the small port of Shirahama, where the island's only road runs out. The boat trip takes about 15 minutes but to walk around the bay would, we're told, take three days of hacking through jungle.

This place would probably be worth a three-day hike, though. Iriomote is the biggest, but least densely populated, of Japan's Yaeyama islands, about 1,200 miles south-west of Tokyo, and much closer to Taiwan than the Japanese mainland. Much of the island is national park, and covered in jungle and mangrove swamps. The western peninsula, on which Funauki sits, is ringed with white-sand beaches, like a scalloped necklace. The closest, Ida, is about a 10-minute walk along a jungle path from the village: dense trees running right down to a perfect coral-strewn shore and clear warm sea.

But this was just nibbling at the edges: on our second day on Iriomote, tour operator Inside Japan Tours, which has launched holidays to the region, had arranged something more adventurous for my husband and me. Climbing into one-man kayaks at Funaura Bay, where two broad brown rivers empty into a wide delta, we headed inland. We were aiming for the 55m-high Pinaisara waterfall, the highest in the region, but our eyes were initially fixed on what was closer to hand: mangroves on leggy stilt roots above ground teeming with fiddler crabs, waving their oversized right claws, hermit crabs of all sizes and thousands of mudskippers – little fish that can walk on land and breathe air.

Though it felt intrepid, kayaking on the rising tide in warm sunshine was easy and peaceful, and soon we were tying up at the base of the waterfall for a dip. Pinaisara means white beard: the falls are supposed to look like the long whiskers of an old man. Climbing to its top was more of a challenge, the narrow path so steep in one place that we had to haul ourselves up on a knotted rope.

Our guide, Nao, had promised lunch at the top. We gazed down at the vertiginous drop of white water, and then out at the jungle, the ribbon of river we had kayaked along, the beach, the ocean and a couple of white-rimmed islands in the distance, and meanwhile Nao did a Mary Poppins act with his rucksack. Out came a camping stove and gas bottle, a little folding windshield, pans, water, bowls, chopsticks and food in packets and boxes. His hot noodle soup with pork, spring onions and pickled ginger may not have been the most elaborate meal we had in Japan, but it was the most welcome. For dessert he produced "lollipops" of super-chilled pineapples on sticks.

The delicious local pineapples are the size of a large apple: grown on patches of cultivated land by the coast, they stick up from their bushes like toilet brushes.

Iriomote's coast is glorious, with dark green cliffs and headlands plunging to blue seas, but its few small settlements are very different. We were surprised to find buildings of solid grey concrete, a youth hostel that looked like a detention centre, and a similarly depressing feel at the island's onsen, or hot spring, the most southerly in Japan – though apparently inside it is lovely.

There are two reasons for this style of building: typhoons and diving. From June to September, the islands are regularly hit by tropical cyclones blowing up from the Philippines. Sturdiness, in building design, wins out over aesthetics. And until recently, the few tourists in Iriomote tended to be scuba divers – passionate about undersea worlds, less so about where they lay their heads.

But that is changing: Hoshino Resort Nirakanai is the island's first luxury hotel, a Bali-esque retreat with 141 rooms, pool, spa and other facilities. We were more taken with our billet, the 15-room Eco Village. My Guardianista ears pricked up at the word eco, but there's nothing particularly green about this hotel – it claims the monicker because it is "immersed in nature", on a deserted beach 40 minutes' drive from the main port. While husband tested the wicker lounger on our wide veranda, I wandered through unfenced lawns past the pool to the sea, picking up bits of broken coral from the sand, watched by crows and a family of goats. The restaurant at Eco Village is particularly fine: each dinner was a stunning array of dishes, some delightfully moreish, such as pork with black sesame and island vegetables; others were just strange, such as raw pig's ear (like chewing rubber bands). Breakfasts were only a little less elaborate.

The main Yaeyama island, Ishigaki, where the airport is located, is a similar mix of tropical lushness and workaday architecture. Ishigaki City, the capital, has a laid-back friendly feel, and is a contrast after frenetic Tokyo.

Stallholders in the covered market urged us to try sugar cane candy (yum), sweetmeats made with the ubiquitous purple sweet potato (don't bother) and salt ice-cream that it would be worth travelling 6,000 miles to taste. Young staff at a downtown restaurant did their best, despite the language barrier. Out came the phone again – we'd have soba (buckwheat noodles) kitsune (fried), not zaru (chilled). We were then pressed to join in a session with a local folk-singer on his banjo-like sanshin. Diners clacked little castanet-like mittsu instruments, everyone swigging beers to regular shouts of "kampai" (cheers).

We'd arrived at our hotel, Nagura Cottages, on a quiet stretch of Ishigaki's east coast, late and hungry a couple of days earlier. Checking in, I had asked the manager if there was a restaurant near by. We must have looked stricken when he told us no, because he added, "There is me. I can do dinner." While we settled into our room, in a villa across the courtyard, Sadoyama got busy behind the bar with knives and pans, and within 20 minutes was serving us a four-course meal that included goya – a bitter gourd pickled to sweet, spicy, sour crunchiness – and what looked like a mound of lettuce with tomato sauce, but turned out to hide a tangle of tasty shredded pork on a bed of rice.

We'd started with bottles of local Ji beer (chilled, but darker than lager) and when Sadoyama brought us, unbidden, two large glasses of the rice spirit awamori, clinking with ice, the evening took on a pleasant glow. Nagura Cottages opened four years ago to cater for scuba divers and is more basic than Eco Village, but with quirky touches such as pretty origami birds, made by Sadoyama in moments when reception's a bit quiet.

In stark contrast to the other islands we'd seen, tiny Taketomi, a 10-minute ferry ride from Ishigaki, looks much as it did when it was part of the Ryukyu kingdom, which ruled these islands until ousted by the Japanese in 1879. Preservation orders have safeguarded a central village of traditional one-storey houses, red tile roofs sporting fierce lion-like shiza statues to ward off evil spirits. Each home sits in a plot of land entirely enclosed by sturdy stone walls – it's a bit like the Yorkshire Dales gone mad.

On the edge of the village we stopped in the flowery garden of a minshuku, (guesthouse) run by a wacky old lady with a towel round her head. We only ordered soft drinks, but she proudly brought out a little dish of pickled green vegetables and another of home-grown tomatoes in a sesame dressing that was so delicious – barioishi, the Japanese equivalent, we managed to say – that I don't think olive oil and balsamic will ever quite cut it in future.

One way of getting around traffic-free Taketomi – it's an oval about 2km by 3km – is on a cart drawn by patient water buffalo, but we rented bikes for the short ride to Kaiji beach in the south-east. This is one of the islands' "star" attractions – literally. The sand here is not ground-up rock, but the five-pointed skeletons of millions of crustaceans barely a millimetre in diameter. You really are walking on tiny white stars. The ocean views, shady trees and warm, pale turquoise water are pretty amazing too.

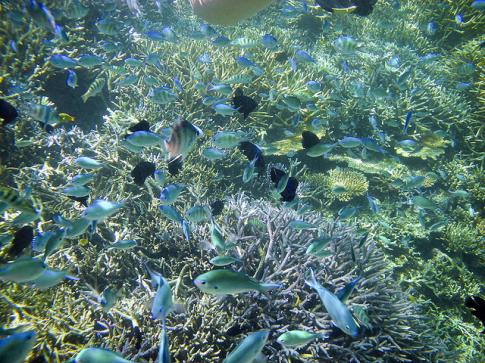

But what's under the sea is obviously the main draw here, so at Umicoza Diving School, back on Ishigaki, we pulled on wetsuits and fins and took a dive boat out into stunning Kabira Bay – the multi-hued water dotted with rocky islets like a mini version of Vietnam's Ha Long Bay (but without the crowds). The couple of qualified divers on the boat tipped off backwards to descend on to the reef, but in these shallow waters we saw just as much with mask and snorkel. Convoluted coral in blue, green, yellow, white – though never pink – and most of the cast of Finding Nemo: triggerfish with white spots on their bellies and perfectly applied luminous yellow lipstick, emperor angelfish in vivid blue and yellow stripes, as well as the famous orange- and white-striped clownfish.

We then climbed back into the boat to head for Manta Point, a little to the west. This is a world-renowned diving spot, where Pacific manta rays of up to four metres across gather to feed on the blooming plankton. Far from deterring them, the presence of divers seems to attract these giants – one theory is the air bubbles tickle a manta's skin. We jumped in and swam about for a bit, but we were unlucky. No mantas showed.

We were not about to complain: the Yaeyamas had already given us so much. The Japanese word for plenty or enough is yoku, and to have griped about not getting more would just have been yokubari – greedy.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment