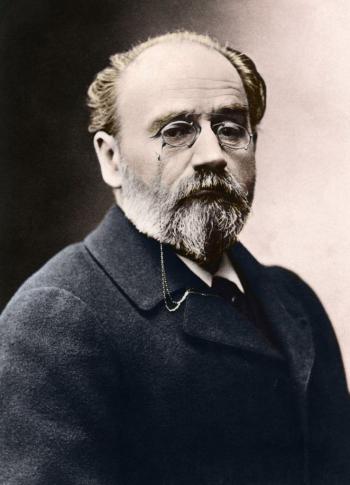

Emile Zola (1840-1902)

Émile Zola was a French novelist, playwright, journalist, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of naturalism...

French novelist and critic, the founder of the Naturalist movement in literature. Zola redefined Naturalism as "Nature seen through a temperament." Among Zola's most important works is his famous Rougon-Macquart cycle (1871-1893), which included such novels as L'ASSOMMOIR (1877), about the suffering of the Parisian working-class, NANA (1880), dealing with prostitution, and GERMINAL (1885), depicting the mining industry. Zola's open letter 'J'accuse,' on January 13, 1898, reopened the case of the Jewish Captain, Alfred Dreyfus, sentenced to Devil's Island.

"I am little concerned with beauty or perfection. I don't care for the great centuries. All I care about is life, struggle, intensity. I am at ease in my generation." (from My Hates, 1866)

Emile Zola was born in Paris. His father, François Zola, was an Italian engineer, who acquired French citizenship. Zola spent his childhood in Aix-en-Provence, southeast France, where the family moved in 1843. When Zola was seven, his father died, leaving the family with money problems – Emilie Aubert, his mother, was largely dependent on a tiny pension. In 1858 Zola moved with her to Paris. In his youth he became friends with the painter Paul Cézanne, who was his class-mate. Zola's widowed mother had planned a career in law for him. Zola, however, failed his baccalaureate examination – as later did the writer Anatole France, who failed several times but finally passed. According to one story, Zola was sometimes so broke that he ate sparrows that he trapped on his window sill.

Zola began to write under the influence of the romantics. Before his breakthrough, Zola worked as a clerk in a shipping firm and then in the sales department of the publishing house of Louis-Christophe-Francois-Hachette. He also contributed literary columns and art reviews to the Cartier de Villemessant's newspapers. Zola supported the struggle of Edouard Manet and Impressionists; Manet thanked him with a portrait. As a political journalist Zola did not hide his antipathy toward the French Emperor Napoleon III, who used the Second Republic as a springboard to become Emperor.

During his formative years Zola wrote several short stories and essays, 4 plays and 3 novels. Among his early books was CONTES Á NINON, which was published in 1864. When his sordid autobiographical novel LA CONFESSION DE CLAUDE (1865) was published and attracted the attention of the police, Zola was fired from Hachette.

Zola did not much believe in the possibility of individual freedom, but emphasized that "events arise fatally, implacably, and men, either with or against their wills, are involved in them. Such is the absolute law of uman progress." Inspired by Claude Bernard's Introduction à la médecine expérimentale (1865) Zola tried to adjust scientific principles in the process of observing society and interpreting it in fiction. Thus a novelist, who gathers and analyzes documents and other material, becomes a part of the scientific research. His treatise, LE ROMAN EXPÉRIMENTAL (1880), manifested the author's faith in science and acceptance of scientific determinism.

After his first major novel, THÉRÈSE RAQUIN (1867), Zola began the long series called Les Rougon Macquart, the natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire. "I want to portray, at the outset of a century of liberty and truth, a family that cannot restrain itself in its rush to possess all the good things that progress is making available and is derailed by its own momentum, the fatal convulsions that accompany the birth of a new world." The family had two branches – the Rougons were small shopkeepers and petty bourgeois, and the Marquarts were poachers and smugglers who had problems with alcohol. Some members of the family would rise during the story to the highest levels of the society, some would fall as victims of social evils and heredity. Zola presented the idea to his publisher in 1868. "The Rougon-Macquart – the group, the family, whom I propose to study – has as its prime characteristic the overflow of appetite, the broad upthrust of our age, which flings itself into enjoyments. Physiologically the members of this family are the slow working-out of accidents to the blood and nervous system which occur in a race after a first organic lesion, according to the environment determining in each of the individuals of this race sentiments, desires, passions, all the natural and instinctive human manifestations whose products take on the conventional names of virtues and vices."

At first the plan was limited to 10 books, but ultimately the series comprised 20 volumes, ranging in subject from the world of peasants and workers to the imperial court. Zola prepared his novels carefully. The result was a combination of precise documentation, accurate portrayals, and dramatic imagination; the last had actually little to do with his Naturalist theories. Zola interviewed experts, prepared thick dossiers, made thoughtful portraits of his protagonists, and outlined the action of each chapter. He rode in the cab of a locomotive when he was preparing LA BÊTE HUMAINE (1890, The Beast in Man), and for Germinal he visited coal mines. This was something very different from Balzac's volcanic creative writing process, which produced La Comédie humaine, a social saga of nearly 100 novels. The Beast in Man was adapted for screen for the first time in 1938. The director, Jean Renoir wrote the screenplay with Zola's daughter, Denise Leblond-Zola. In the film Séverine (Simone Simon) wants her lover, the locomotive engineer Lantier (Jean Gabin), to kill her stationmaster husband. Lentier, an honest and proud man, cannot do it, but in a fit of anger and frustration he strangles his beloved instead and commits suicide by throwing himself off a fast moving train.

With L'Assommoir (1877, Drunkard), a depiction of alcoholism, Zola became the best-known writer in France, who attracted crowds imitators and disciples, to his great annoyance: "I want to shout out from the housetops that I am not a chef d'ecole, and that I don't want any disciples," Zola once said. His personal appearance – once somebody said that he had the head of a philosopher and the body of an athlete – was know to everybody. Following the publication of LES SOIRÉES DE MÉDAN (1880), Guy de Maupassant jokingly suggested that Zola's country house at Médan should be visited with the same intrerest as the Palace of Versailles and other historical places. Zola lived there eight months in the year, and the other four month in Paris.

Nana, about a young Parisian prostitute, took the reader to the world of sexual exploitation. In general, sex was a central element in Zola's novels. The book was a huge success in France but in Britain it was attacked by moralist. Henry Vizetelly, who had published several Zola translations from the Rougon-Macquart series, was imprisoned on charges of obscenity. The translation of LA TERRE (1887) practically ruined Vizetelly & Company. Germinal, one of Zola's finest novels, came out in 1885. It was the first major work on a strike, based on his research notes on labor conditions in the coal mines. Germinal was criticized by right-wing political groups as a call to revolution. Zola's tetralogy, LES QUATRE EVANGILES, which started with FÉCONDITÉ (1899), was left unfinished.

Also notable in Zola's career was his involvement in the Dreyfus affair with his open letter J'ACCUSE. "In making these accusations, I am fully aware that my action comes under Articles 30 and 31 of the law of 29 July 1881 on the press, which makes libel a punishable offence," Zola wrote challenging. Alfred Dreyfus (1859-1935) was a French Jewish army officer, who was falsely charged with giving military secrets to the Germans. The trials quickly developed into a idealogical struggle, or as Anatole France wrote, "rendered an inestimable service to the country by bringing out and little by little revealing the forces of past and the forces of future: on the one side bourgeois authoritarianism and Catholic theocracy; on the other side socialism and free thought." Dreyfus was transported to Devil's Island in French Guiana. The case was tried again in 1899 and he was found first guilty and pardoned, but later the verdict was reversed. "The truth is on the march, and nothing shall stop it," Zola announced, but during the process he was sentenced in 1898 to imprisonment and removed from the roll of the Legion of Honor. He escaped to England, and returned after Dreyfus had been cleared.

Zola died on September 28, in 1902, under mysterious circumstances, overcome by carbon monoxide fumes in his sleep. According to some speculations, Zola's enemies blocked the chimney of his apartment, causing poisonous fumes to build up and kill him. At Zola's funeral Anatole France declared, "He was a moment of the human conscience." In 1908 Zola's remains were transported to the Panthéon. Naturalism as a literary movement fell out of favor after Zola's death, but his integrity had a profound influence on such writers as Theodore Dreiser, August Strindberg and Emilia Pardo-Bazan.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us Digg

Digg

Post your comment